The Joy of Trump

Vancouver Island Eyes on the World

Friday, February 26, 2016

Sunday, February 21, 2016

A Sense of Wonder

“A knowledge of the existence of something we cannot penetrate, of the manifestations of the profoundest reason and the most radiant beauty, which are only accessible to our reason in their most elementary forms—it is this knowledge and this emotion that constitute the truly religious attitude; in this sense, and in this alone, I am a deeply religious man”

- Albert Einstein

Saturday, February 13, 2016

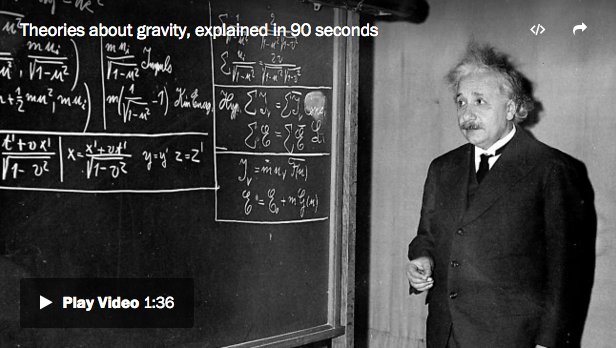

A brief history of gravity, gravitational waves - Albert Einsein

A brief history of gravity, gravitational waves and #LIGO: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2016/02/11/a-brief-history-of-gravity/ …

Thursday, February 11, 2016

The Little-Known Recording Trick That Makes Singers Sound Perfect

Written by

Meghan Neal

Put on a Taylor Swift or Mariah Carey or Michael Jackson song

and listen to the vocals. You may think the track was recorded by the

artist singing the song through a few times and the producer choosing

the best take to use on the record. But that’s almost never the case.

The reality is far less romantic. Listen to almost any contemporary pop or rock record and there’s a very good chance the vocals were “comped.” This is when the producer or sound engineer combs through several takes of the vocal track and cherry-picks the best phrases, words, or even syllables of each recording, then stitches them together into one flawless “composite” master track.

Though it’s unknown to most listeners, comping’s been standard practice in the recording industry for decades. Everyone does it—“even the best best best best singers,” says producer and mix engineer Ken Lewis, who’s comped vocals for Mary J Blige, Usher, David Byrne, Lenny Kravitz, Ludacris, Soul Asylum, Diana Ross, and Queen Latifah.

But surely cobbling together a song this way must sound disjointed, robotic, devoid of personality, right? That’s certainly what I thought when I first learned about the practice. And while it’s true that vocal comping is used heavily in pop music where the intention is usually to sound smooth and polished rather than honest and gritty, most producers will tell you that this piecemeal approach is the best way to get a superb recording from any vocalist.

“This is the epitome of all that is unglamorous in music, but very necessary for the best possible presentation of the most important element in the mix,” wrote music producer Frank Gryner in Recording Magazine. He’s recorded the likes of Rob Zombie and Tommy Lee. “I’ve yet to work on a major-label record that didn’t involve vocal comping to arrive at the finished product.”

The process works like this: A singer records the song through a handful of times in the studio, either from start to finish or isolating particularly tricky spots. Starting with between 4-10 takes is typical—too many passes can drain the artist’s energy and confidence and also bog down the editing process later. (That said, it’s sometimes much more. Christina Aguilera’s song “Here to Stay” was compiled from 100 different takes. “She sat on the stool and sang the song for six hours until it was done—didn't leave the booth once and didn't make a single phone call,” engineer Ben Allen said in an interview with Tape Op magazine.)

The engineer generally follows along during the studio recording with a lyric sheet and jots down notes to use as a guide for later, marking whether a phrase was very good, good, bad, sharp or flat, and so on.

When the session’s over, they listen closely to each section of

each take, playing the line back on loop with the volume jacked up twice

as high as it will be in the final mix. They’re listening to make sure

the singer’s on pitch, of course, but that’s not necessarily the primary

measure of what makes the final cut.

When the session’s over, they listen closely to each section of

each take, playing the line back on loop with the volume jacked up twice

as high as it will be in the final mix. They’re listening to make sure

the singer’s on pitch, of course, but that’s not necessarily the primary

measure of what makes the final cut.

Timing, tone, attitude, emotion, personality, and how each phrase or word fits in context with the other instruments and the rest of the vocal track can trump pitch perfection. Those little quirky gems add character and emotion to the track—they’re what the listener remembers.

The recording engineer picks out the best take for each bit of the song and edits all the pieces together, usually in a digital audio workstation (DAW) like Pro Tools.

“Often, I’ll have a three-syllable word in the middle of a line, and I’ll use the first syllable from take 3, the second syllable from take 7, and the third syllable from take 10," Lewis writes in a blog post. “Not kidding.”

Most programs today let you input multiple files within an audio track, so you can simply drag and drop the portion you want from each take into the master track.

“It’s rare that you hear a really bad vocal comp,” says says recording engineer Mike Senior, a columnist for Sound on Sound and author of Mixing Secrets for the Small Studio. But that’s often because the edits are obscured by the other instruments in the track.

About 20 seconds into Aguilera’s “Genie in the Bottle” is a really clunky edit, but you can’t hear it in the song because it’s tucked behind a big heavy drum beat, says Senior. “If you think how many drum beats typically occur in a mainstream song, you can think how many places you can edit without it being heard.”

Listen closely to Adele’s hit “Someone Like You” and you can hear that in the first couple verses the opening breath is missing—there’s just no breath on that phrase, he points out. You can also hear some background noise on the mic throughout the song but then in certain places it cuts out, a sign of an edit.

As

you can imagine, the whole process is incredibly tedious and time

consuming; it can take hours, even days. “That’s why these records are

expensive,” said engineer Mark Bright in an interview with Bobby

Owsinski, author of The Music Producer’s Handbook.Blight

has produced Carrie Underwood, Reba McEntyre, and Rascal Flatts, and

typically spends 8-12 hours comping a track from upwards of 20 takes.

Max Martin and “Dr. Luke” Gottwald, the hitmakers behind mega pop stars like Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry and Britney Spears, are known for relying heavily on comping during their recording process. John Seabrook, author of The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory, writes in the New Yorker: “Comping is so mind-numbing boring that even Gottwald, with his powers of concentration, can’t tolerate it.” However, "Max loves comping," songwriter Bonnie McKee told Seabrook. "He’ll do it for hours.’”

But while pop songs are often accused of being sterile, artificial, or overproduced, each producer I talked to said this is not the result of comping. “Comping is not the thing that makes something sound robotic. Actually I would say comping does the opposite,” says Senior.

Comping gets a bad rap because it’s lumped in with other editing tools like pitch correction and auto-tune, but “it is almost unreservedly a good thing,” Senior says. It gives singers the freedom to push the boundaries and perform at the edge of their capability, trusting it’s OK to mess up because there’s the safety net of having multiple other takes. And if there is a rogue bum note in an otherwise killer recording, you can swap it out with an on pitch note from another take instead of relying on pitch correction, which alters the overall sonic quality.

Pushing the limit and taking chances is what leads to those gems that can make a whole track, says Lewis. “That’s one of the beauties of comping—you get to search for the most magical piece of every take.”

“People have a very idealistic view of a producer or recording engineer’s job. If people really knew how records were made, they’d be much more jaded,” says Lewis. “But if you go into record making with the idea that you need to sing the song down from start to finish, come what may, you will rarely find the true magic.”

The reality is far less romantic. Listen to almost any contemporary pop or rock record and there’s a very good chance the vocals were “comped.” This is when the producer or sound engineer combs through several takes of the vocal track and cherry-picks the best phrases, words, or even syllables of each recording, then stitches them together into one flawless “composite” master track.

Though it’s unknown to most listeners, comping’s been standard practice in the recording industry for decades. Everyone does it—“even the best best best best singers,” says producer and mix engineer Ken Lewis, who’s comped vocals for Mary J Blige, Usher, David Byrne, Lenny Kravitz, Ludacris, Soul Asylum, Diana Ross, and Queen Latifah.

“Comping doesn’t have to do with the quality of the vocalist,” Lewis says. “Back in the Michael Jackson days—and Michael Jackson was an incredible singer—they used to comp 48 tracks together, from what I’ve read and what I’ve heard.”“Comping is not the thing that makes something sound robotic. Actually I would say it does the opposite."

But surely cobbling together a song this way must sound disjointed, robotic, devoid of personality, right? That’s certainly what I thought when I first learned about the practice. And while it’s true that vocal comping is used heavily in pop music where the intention is usually to sound smooth and polished rather than honest and gritty, most producers will tell you that this piecemeal approach is the best way to get a superb recording from any vocalist.

“This is the epitome of all that is unglamorous in music, but very necessary for the best possible presentation of the most important element in the mix,” wrote music producer Frank Gryner in Recording Magazine. He’s recorded the likes of Rob Zombie and Tommy Lee. “I’ve yet to work on a major-label record that didn’t involve vocal comping to arrive at the finished product.”

The process works like this: A singer records the song through a handful of times in the studio, either from start to finish or isolating particularly tricky spots. Starting with between 4-10 takes is typical—too many passes can drain the artist’s energy and confidence and also bog down the editing process later. (That said, it’s sometimes much more. Christina Aguilera’s song “Here to Stay” was compiled from 100 different takes. “She sat on the stool and sang the song for six hours until it was done—didn't leave the booth once and didn't make a single phone call,” engineer Ben Allen said in an interview with Tape Op magazine.)

The engineer generally follows along during the studio recording with a lyric sheet and jots down notes to use as a guide for later, marking whether a phrase was very good, good, bad, sharp or flat, and so on.

↑ = sharp ↓ = flat G = good VG = very good X = bad ? = “I can’t decide.” Image: The Music Producer’s Handbook by Bobby Owsinski

An example of a comp sheet for lead

vocal. The columns on the right indicate promising sections of the eight

takes and final decisions are noted over the lyrics. Image: Mixing Secrets for the Small Studio by Mike Senior.

Timing, tone, attitude, emotion, personality, and how each phrase or word fits in context with the other instruments and the rest of the vocal track can trump pitch perfection. Those little quirky gems add character and emotion to the track—they’re what the listener remembers.

The recording engineer picks out the best take for each bit of the song and edits all the pieces together, usually in a digital audio workstation (DAW) like Pro Tools.

“Often, I’ll have a three-syllable word in the middle of a line, and I’ll use the first syllable from take 3, the second syllable from take 7, and the third syllable from take 10," Lewis writes in a blog post. “Not kidding.”

Comping is one of the most common DAW tasks and the software has made it stupid simple, especially compared to cutting tape reels back in the analog days, when editors would mark the cut spot on the open tape reel with a pencil, slice it with a razor blade and attach the two ends together with sticky tape.Christina Aguilera’s song “Here to Stay” was compiled from 100 different takes.

Most programs today let you input multiple files within an audio track, so you can simply drag and drop the portion you want from each take into the master track.

Comping tutorial in Pro Tools. GIF via YouTube

The editor makes sure the transitions are seamless, the track

flows properly, that no glitches or bad edits made it into the final

cut, and importantly, that no emotion or personality is lost in the

process. A sign of a success is that the listener has no idea a song’s

vocals were compiled from several different takes. The work should be

invisible.“It’s rare that you hear a really bad vocal comp,” says says recording engineer Mike Senior, a columnist for Sound on Sound and author of Mixing Secrets for the Small Studio. But that’s often because the edits are obscured by the other instruments in the track.

About 20 seconds into Aguilera’s “Genie in the Bottle” is a really clunky edit, but you can’t hear it in the song because it’s tucked behind a big heavy drum beat, says Senior. “If you think how many drum beats typically occur in a mainstream song, you can think how many places you can edit without it being heard.”

Listen closely to Adele’s hit “Someone Like You” and you can hear that in the first couple verses the opening breath is missing—there’s just no breath on that phrase, he points out. You can also hear some background noise on the mic throughout the song but then in certain places it cuts out, a sign of an edit.

Max Martin and “Dr. Luke” Gottwald, the hitmakers behind mega pop stars like Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry and Britney Spears, are known for relying heavily on comping during their recording process. John Seabrook, author of The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory, writes in the New Yorker: “Comping is so mind-numbing boring that even Gottwald, with his powers of concentration, can’t tolerate it.” However, "Max loves comping," songwriter Bonnie McKee told Seabrook. "He’ll do it for hours.’”

But while pop songs are often accused of being sterile, artificial, or overproduced, each producer I talked to said this is not the result of comping. “Comping is not the thing that makes something sound robotic. Actually I would say comping does the opposite,” says Senior.

Comping gets a bad rap because it’s lumped in with other editing tools like pitch correction and auto-tune, but “it is almost unreservedly a good thing,” Senior says. It gives singers the freedom to push the boundaries and perform at the edge of their capability, trusting it’s OK to mess up because there’s the safety net of having multiple other takes. And if there is a rogue bum note in an otherwise killer recording, you can swap it out with an on pitch note from another take instead of relying on pitch correction, which alters the overall sonic quality.

Pushing the limit and taking chances is what leads to those gems that can make a whole track, says Lewis. “That’s one of the beauties of comping—you get to search for the most magical piece of every take.”

“People have a very idealistic view of a producer or recording engineer’s job. If people really knew how records were made, they’d be much more jaded,” says Lewis. “But if you go into record making with the idea that you need to sing the song down from start to finish, come what may, you will rarely find the true magic.”

You can reach us at letters@motherboard.tv. Want to see other people talking

about Motherboard? Check out our letters to the editor.

The Little-Known Recording Trick That Makes Singers Sound Perfect

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)