Henry A. Kissinger was secretary of state from 1973 to 1977.

The Joy of Trump

Vancouver Island Eyes on the World

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Detroit is worse than Mexico or Thailand

One surprising way Detroit is worse than Mexico or Thailand

Friday, June 27, 2014

Tabloids

Financial Times @FT

Financial Times @FT Era of the Fleet Street tabloids, populist and fearsome emblems of British culture, is over

Afghanistan and the Growing Risks in Transition

WASHINGTON, June 26, 2014 - The Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) Burke Chair in Strategy has prepared three related reports that illustrate the current security threats in stabilizing the Afghan security forces; the post-election challenges to Afghan reconstruction; and the challenges facing Afghan governance and the Afghan economy.

Please find links to download the reports below:

Report One: The Post-Election Challenges to Afghan Transition: 2014-2015

Report Two:Security Transition in Afghanistan

Report Three: Governance and Economic Transition in Afghanistan

Read the summary as prepared by the author:

These reports all show a rising risk that Transition will fail. They show that the "surge" in Afghanistan did not achieve anything like the positive results that the surge in Iraq achieved before U.S. and allied forces left, and that Afghan security forces still have critical problems in quality and funding. These are problems that President Obama largely discounted in his May 27, 2014 speech on Transition in Afghanistan:

From President Obama, May 27, 2014, on transition in Afghanistan:"...Our objectives are clear: Disrupting threats posed by al-Qaeda; supporting Afghan security forces; and giving the Afghan people the opportunity to succeed as they stand on their own.

"Here's how we will pursue those objectives. First, America's combat mission will be over by the end of this year. Starting next year, Afghans will be fully responsible for securing their own country. American personnel will be in an advisory role. We will no longer patrol Afghan cities of towns, mountains or valleys. That is a task for the Afghan people.

"Second, I've made it clear that we're open to cooperating with Afghans on two narrow missions after 2014: training Afghan forces and supporting counter-terrorism operations against the remnant of al-Qaeda.

"Today, I want to be clear about how the United States is prepared to advance those missions. At the beginning of 2015, we will have approximately 98,000 U.S. -- let me start that over, just because I want to make sure we don't get this written wrong. At the beginning of 2015, we will have approximately 9,800 U.S. service members in different parts of the country, together with our NATO allies and other partners. By the end of 2015, we will have reduced that presence y roughly half, and we will have consolidated our troops in Kabul and on Bagram Airfield. One year later, by the end of 2016, our military will draw down to a normal embassy presence in Kabul, with a security assistance component, just as we've done in Iraq.

"Now, even as our troops come home, the international community will continue to support Afghans as they build their country for years to come. But our relationship will not be defined by war -- it will be shaped by our financial ad development assistance, as well as our diplomatic support. Our commitment to Afghanistan is rooted in the strategic partnership that we agreed to in 2012. And this plan remains consistent with discussions we've had with our NATO allies. Just as our allies have been with us every step of the way in Afghanistan, we expect that our allies will be with us going forward.

"Third, we will only sustain this military presence after 2014 if the Afghan government signs the Bilateral Security Agreement that our two governments have already negotiated. This Agreement is essential to give our troops the authorities they need to fulfill their mission, while respecting Afghan sovereignty. The two final Afghan candidates in the run-off election for President have each indicated that they would sign this agreements promptly after taking office. So I'm hopeful that we can get this done."

In spite of the rushed and uncertain character of the Afghan force development, the president chose to provide the minimum recommended mix of U.S. advisors, enablers, and counterinsurgency forces recommended by ISAF for only one year. This, in spite of the fact that the U.S. military has consistently understated the need for advisors, aid, and prolonged effort in their past plans in Vietnam, Iraq, and other operations.

More generally, he did not address either military or civil aid issues, focused solely on the election as a measure of governance, established no condition for aid and support other than Afghan agreement to a bilateral security agreement, and did not address economic risk, the problems posed by sanctuaries in Pakistan and Pakistan's part actions. The White House also issued a "Fact Sheet" that repeated past claims to progress in "Afghanistan" that are uncertain, false, or taken out of context.

As the data in these reports show, the end result is to grossly understate the risks facing our Afghan ally, and to repeat the false estimates of progress or "follies" the U.S. issued in Vietnam and towards the end of the fighting in Iraq. These kinds of Assessments make the U.S. a potential threat to its own interests, and are the same failures, oversights, and shortcomings that Neil Sheehan described in his critique of U.S. folly in Vietnam, A Bright and Shining Lie.

The range of metrics and data in The Post-Election Challenges to Afghan Transition: 2014-2015, and its sub-reports, can only cover part of this story, but they do provide a wide range of warnings of just how serious the risks in Transition really are. In practice, both these risks and the prospect of some form of failure in Afghanistan may be acceptable. The U.S. has higher strategic priorities in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, and finite resources. It has a weak and uncertain Afghan partner, and one that has yet to sow it can develop either effective leadership or effective governance.

At the same time, there are enough positive trends in Afghan forces, governance, and economics to show that a still limited but more realistic level of U.S. effort might produce a relatively stable Afghanistan. A more realistic effort to support Afghan forces might offer a higher prospect of success, and the same World Bank reporting that provides a levels of realism on Afghan governance and economics is sadly lacking the U.S. official reporting present in past reports, including Islamic State of Afghanistan: Pathways to Inclusive Growth. That report offers a far more realistic and affordable path to acceptable levels of Afghan governance and economics that dreams of a new Silk Road or sudden wealth in exploiting national resources.

For all of the negative trends and warnings issued in the three Burke Chair reports, there are potentially affordable options that can prevent U.S. withdrawal from repeating the experience in Vietnam and Iraq and from ending in either a bang or a whimper.

###

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) is a bipartisan, non-profit organization founded in 1962 and headquartered in Washington, D.C. It seeks to advance global security and prosperity by providing strategic insights and policy solutions to decision makers

Thursday, June 26, 2014

Carl Jung

Anyone who wants to know the human psyche will learn next to nothing from experimental psychology. He would be better advised to abandon exact science, put away his scholar's gown, bid farewell to his study, and wander with human heart through out the world. There in the horrors of prisons, lunatic asylums and hospitals, in drab suburban pubs, in brothels and gambling-hells, in the salons of the elegant, the Stock Exchanges, socialist meetings, churches, revivalist gatherings and ecstatic sects, through love and hate, through the experience of passion in every form in his own body, he would reap richer stores of knowledge than text-books a foot thick could give him, and he will know how to doctor the sick with a real knowledge of the human soul. -- Carl Jung

From Among Whales, by Roger Payne

From Among Whales, by Roger Payne

Primates are a group of closely related species for which the social systems of many species are well understood and for which the ratio of testes size to body weight is also well known. For example, chimpanzees have a multiple male mating system. When she comes into estrus, a female chimpanzee mates with many males. Although the bodies of chimps are smaller than

most human bodies, male chimpanzees have larger testes than we do.

Gorillas have a single-male mating system. Once he has fought his way to ownership of a troupe of females, a silver-back male has sole access to females in his group. Even though they are much larger than chimpanzees, male gorillas have testes so small that during a dissection the testes are difficult to locate.

When the ratio is plotted of testes weight to body weight for the thirty- three primate species for which both the social systems and these ratios are known, one gets a cloud of points. When a median line is fitted through the cloud, the species above the line all have large testes in relation to their body size, and the species below small testes in relation to their body size.28

A fascinating fact emerges: the primate species above the line have multiple-male mating systems, while those below it have single-male mating systems. Apparently the mating system determines how large a male’s testes will be relative to his body size. The ratio of testes size to body weight thus provides a valuable clue to the breeding systems of primate species whose mating systems are not known.

Potentially, this result has social significance for humans, for we are primates and therefore our testes size should tell us which social system our ancestors favored: polyandry, in which a woman has several mates (the multiple-male mating system); or polygyny, in which a man has several mates (the single-male mating system). It turns out that in humans the ratio of testes size to body weight is neither high nor low. The human ratio lies practically on the line separating polyandrous mating systems from polygynous mating systems. How fascinating: it means that our species never made a clear choice of mating system that would have placed us unambiguously in one of the two systems. Given the shattering effects wrought on our lives throughout human history by this ambiguity, it is interesting that we still seem so undecided.

Among Whales

Outlaw Neonicotinoid Pesticides

Alexandra Sedgwick

Communications Coordinator

Environmental Justice Foundation

THE BEE COALITION: URGES GOVERNMENT TO REJECT SYNGENTA BID TO USE BANNED PESTICIDE

On the day the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides announced their report on confirming the clear damaging effects of neonicotinoids on pollinators, Syngenta has asked to be allowed to use one of its currently banned neonicotinoid pesticides on 186,000 hectares of oil seed rape in the UK.

The news of this request for a derogation emerged at a Council Meeting of the National Farmers Union, which appears to support the request by Syngenta and also opposes the EC’s restriction on neonicotinoids.

Any such derogation, which has been asked for to control flea beetle, will undermine the temporary ban on the use of neonicotinoids imposed by the EU at the end of last year, making it even more difficult to assess the true impact of neonicotinoids on pollinators than was already the case.

Nick Mole of Pesticide Action Network UK, a member of the Bee Coalition said; "This is a clear attempt by Syngenta and the NFU to undermine the EU ban which they so bitterly opposed by the back door.”

Steve Trent of Environmental Justice Foundation, a member of the Bee Coalition said; "In light of today's report it is imperative that the UK Government reject this request from Syngenta to use a banned pesticide which we know will be harmful to the UK's pollinators and will undermine the effective monitoring of the neonicotinoid ban in the UK."

The Bee Coalition regards Syngenta’s request as a deliberate attempt to undermine the EC’s temporary restriction on three of the main neonicotinoids, does not believe there is a justification for this derogation and urgently calls on DEFRA to reject this request.

NOTES FOR EDITORS:

It is thought that Syngenta, supported by the NFU, is seeking a quick decision from the UK Environment Department (Defra) to allow it to derogate from current EU restriction on three of the main neonicotinoids used in farming mainly as seed treatments before seed has to be sown in the ground by 14 August 2014. The request emerged on the same day that the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides released its review of evidence of the effect of neonicotinoids on bees, wildlife, soils and water - http://www.tfsp.info/

A 2014 review of US literature by the Center for Food Safety concluded that neonicotinoid seed treatments do not deliver significant yield benefits in many contexts. It concluded “In sum, we found that numerous studies show neonicotinoid seed treatments do not provide significant yield benefits in many contexts. European reports of crop yields being maintained even after regional neonicotinoid bans corroborate this finding. Opinions from several independent experts reinforce that neonicotinoids are massively overused in the US, without a corresponding yield benefit, across numerous agricultural contexts. The bottom line is that toxic insecticides are being unnecessarily applied in most cases.” Heavy Costs. Weighing the Value of Neonicotinoid Insecticides in Agriculture. S Stevens & P Jenkins, Center for Food Safety, US, 2014. http://www.

The Bee Coalition formed in 2012 when the UK’s main environmental groups joined forces to call for a ban on neonicotinoid pesticides that are toxic to bees and pollinators. Since 2012, a core group of eight organisations (Buglife, Client Earth, Environmental Justice Foundation, Friends of the Earth, Natural Beekeeping Trust, Pesticide Action Network, RSPB and Soil Association) have been working to bring attention to the plight of bees and pollinators and specifically to engage policymakers, industry and the public about their respective roles in ensuring their protection.-------------------

This message was sent to Robert. If you no longer wish to receive email from us, please follow the link below or copy and paste the entire link into your browser. http://www.xmr3.com/rm/

Communications Coordinator

Environmental Justice Foundation

THE BEE COALITION: URGES GOVERNMENT TO REJECT SYNGENTA BID TO USE BANNED PESTICIDE

On the day the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides announced their report on confirming the clear damaging effects of neonicotinoids on pollinators, Syngenta has asked to be allowed to use one of its currently banned neonicotinoid pesticides on 186,000 hectares of oil seed rape in the UK.

The news of this request for a derogation emerged at a Council Meeting of the National Farmers Union, which appears to support the request by Syngenta and also opposes the EC’s restriction on neonicotinoids.

Any such derogation, which has been asked for to control flea beetle, will undermine the temporary ban on the use of neonicotinoids imposed by the EU at the end of last year, making it even more difficult to assess the true impact of neonicotinoids on pollinators than was already the case.

Nick Mole of Pesticide Action Network UK, a member of the Bee Coalition said; "This is a clear attempt by Syngenta and the NFU to undermine the EU ban which they so bitterly opposed by the back door.”

Steve Trent of Environmental Justice Foundation, a member of the Bee Coalition said; "In light of today's report it is imperative that the UK Government reject this request from Syngenta to use a banned pesticide which we know will be harmful to the UK's pollinators and will undermine the effective monitoring of the neonicotinoid ban in the UK."

The Bee Coalition regards Syngenta’s request as a deliberate attempt to undermine the EC’s temporary restriction on three of the main neonicotinoids, does not believe there is a justification for this derogation and urgently calls on DEFRA to reject this request.

NOTES FOR EDITORS:

It is thought that Syngenta, supported by the NFU, is seeking a quick decision from the UK Environment Department (Defra) to allow it to derogate from current EU restriction on three of the main neonicotinoids used in farming mainly as seed treatments before seed has to be sown in the ground by 14 August 2014. The request emerged on the same day that the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides released its review of evidence of the effect of neonicotinoids on bees, wildlife, soils and water - http://www.tfsp.info/

A 2014 review of US literature by the Center for Food Safety concluded that neonicotinoid seed treatments do not deliver significant yield benefits in many contexts. It concluded “In sum, we found that numerous studies show neonicotinoid seed treatments do not provide significant yield benefits in many contexts. European reports of crop yields being maintained even after regional neonicotinoid bans corroborate this finding. Opinions from several independent experts reinforce that neonicotinoids are massively overused in the US, without a corresponding yield benefit, across numerous agricultural contexts. The bottom line is that toxic insecticides are being unnecessarily applied in most cases.” Heavy Costs. Weighing the Value of Neonicotinoid Insecticides in Agriculture. S Stevens & P Jenkins, Center for Food Safety, US, 2014. http://www.

The Bee Coalition formed in 2012 when the UK’s main environmental groups joined forces to call for a ban on neonicotinoid pesticides that are toxic to bees and pollinators. Since 2012, a core group of eight organisations (Buglife, Client Earth, Environmental Justice Foundation, Friends of the Earth, Natural Beekeeping Trust, Pesticide Action Network, RSPB and Soil Association) have been working to bring attention to the plight of bees and pollinators and specifically to engage policymakers, industry and the public about their respective roles in ensuring their protection.-------------------

This message was sent to Robert. If you no longer wish to receive email from us, please follow the link below or copy and paste the entire link into your browser. http://www.xmr3.com/rm/

Aquarium Fish

#Hawaii at center of battle over aquarium fish trade http://wapo.st/1iIzach

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

Christopher Ryan: Sexual Omnivores

Published on Feb 20, 2014

An idea permeates our modern view of relationships: that men and women have always paired off in sexually exclusive relationships. But before the dawn of agriculture, humans may actually have been quite promiscuous. Author Christopher Ryan walks us through the

controversial evidence that human beings are sexual omnivores by nature, in hopes that a more nuanced understanding may put an end to discrimination, shame and the kind of unrealistic expectations that kill relationships.

TEDTalks is a daily video podcast of the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world's leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes (or less). Look for talks on Technology, Entertainment and Design -- plus science, business, global issues, the arts and much more.

Find closed captions and translated subtitles in many languages athttp://www.ted.com/translate

Follow TED news on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/tednews

Like TED on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TED

Subscribe to our channel:http://www.youtube.com/user/TEDtalksD...

TEDTalks is a daily video podcast of the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world's leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes (or less). Look for talks on Technology, Entertainment and Design -- plus science, business, global issues, the arts and much more.

Find closed captions and translated subtitles in many languages athttp://www.ted.com/translate

Follow TED news on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/tednews

Like TED on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TED

Subscribe to our channel:http://www.youtube.com/user/TEDtalksD...

Category

License

Standard YouTube License

Link:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LJhklPJz9U8&list=UUAuUUnT6oDeKwE6v1NGQxug&feature=share&index=21

Monday, June 23, 2014

Ukraine

How the Ukraine crisis ends

By Henry A. Kissinger, Published: March 5

Far too often the Ukrainian issue is posed as a showdown: whether Ukraine joins the East or the West. But if Ukraine is to survive and thrive, it must not be either side’s outpost against the other — it should function as a bridge between them.

The West must understand that, to Russia, Ukraine can never be just a foreign country. Russian history began in what was called Kievan-Rus. The Russian religion spread from there.

The European Union must recognize that its bureaucratic dilatoriness and subordination of the strategic element to domestic politics in negotiating Ukraine’s relationship to Europe contributed to turning a negotiation into a crisis. Foreign policy is the art of establishing priorities.

The Ukrainians are the decisive element. They live in a country with a complex history and a polyglot composition. The Western part was incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1939 , when Stalin and Hitler divided up the spoils. Crimea, 60 percent of whose population is Russian , became part of Ukraine only in 1954 , when Nikita Khrushchev, a Ukrainian by birth, awarded it as part of the 300th-year celebration of a Russian agreement with the Cossacks.

Russia and the West, and least of all the various factions in Ukraine, have not acted on this principle. Each has made the situation worse. Russia would not be able to impose a military solution without isolating itself at a time when many of its borders are already precarious. For the West, the demonization of Vladimir Putin is not a policy; it is an alibi for the absence of one.

Putin should come to realize that, whatever his grievances, a policy of military impositions would produce another Cold War. For its part, the United States needs to avoid treating Russia as an aberrant to be patiently taught rules of conduct established by Washington.

Leaders of all sides should return to examining outcomes, not compete in posturing.

1. Ukraine should have the right to choose freely its economic and political associations, including with Europe.

2. Ukraine should not join NATO, a position I took seven years ago, when it last came up.

3. Ukraine should be free to create any government compatible with the expressed will of its people. Wise Ukrainian leaders would then opt for a policy of reconciliation between the various parts of their country. Internationally, they should pursue a posture comparable to that of Finland. That nation leaves no doubt about its fierce independence and cooperates with the West in most fields but carefully avoids institutional hostility toward Russia.

4. It is incompatible with the rules of the existing world order for Russia to annex Crimea. But it should be possible to put Crimea’s relationship to Ukraine on a less fraught basis. To that end, Russia would recognize Ukraine’s sovereignty over Crimea. Ukraine should reinforce Crimea’s autonomy in elections held in the presence of international observers. The process would include removing any ambiguities about the status of the Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol.

These are principles, not prescriptions. People familiar with the region will know that not all of them will be palatable to all parties. The test is not absolute satisfaction but balanced dissatisfaction. If some solution based on these or comparable elements is not achieved, the drift toward confrontation will accelerate. The time for that will come soon enough.

China tops in Corporate Debt Issuance

Wall Street Journal @WSJ

China has overtaken the U.S. as the world's largest corporate debt issuer. http://on.wsj.com/1ytPT7Z

China Tops U.S. in Corporate Debt Issuance

SandP Warns Slowing Economy, Weaker Financial Conditions Pose Risks

SHANGHAI—China has overtaken the U.S. as the world's largest issuer of corporate debt, but a slowing Chinese economy and the weakened financial health of its companies are creating risks globally, according to Standard & Poor's Ratings Services.

The assessment by the U.S. rating firm echoes

increasing concerns over the health of China's financial system, as stresses rise among struggling property developers and cash-strapped local governments.

Adding to the worries is the fact that Beijing has started allowing some small, private borrowers to default on loans and bonds, suggesting a reduced willingness by the state to bail out troubled firms.

increasing concerns over the health of China's financial system, as stresses rise among struggling property developers and cash-strapped local governments.

Adding to the worries is the fact that Beijing has started allowing some small, private borrowers to default on loans and bonds, suggesting a reduced willingness by the state to bail out troubled firms.

In a report released on Monday, S&P said it expects companies around the world to seek up to $60 trillion in new debt and refinancing between 2014 and 2018, an increase from an estimated $53 trillion for the 2013-2017 period. Asian-Pacific corporate issuers will likely account for half of the $60 trillion, and more than half of the $72 trillion in debt the ratings company projects will be outstanding in 2018.

China now has more corporate debt outstanding than any other country, having surpassed the U.S. in 2013, a year sooner than S&P originally expected, the rating firm said.

Although Beijing has tried to rein in credit growth to reshape an economy that has depended on big investments, such as infrastructure projects, an abundant supply of cash at Chinese banks and large capital expenditures by state-owned enterprises have allowed corporate debt to build up quickly in recent years, it said.

S&P said it estimates corporate debt outstanding in China was $14.2 trillion at the end of 2013, compared with $13.1 trillion in the U.S. China's new debt and refinancing needs are expected to reach $20.4 trillion in 2018, around one-third of the world's total at that time, while the U.S.'s will likely be about $14 trillion.

"The combination of weakened financial profiles, slower economic growth, tighter access to borrowing, and higher interest rates pose a significant challenge to China's corporate borrowers, especially the small-to-medium enterprises," SandP said.

"As the world's second-largest economy, any significant reverse for China's corporate sector could quickly spread to other countries."

Citing findings of a study it conducted comparing more than 8,500 listed Chinese and foreign companies, S&P said that while China's companies started 2009 better off than their global peers, their cash flow and leverage have worsened in subsequent years. Their ability to repay their debt has weakened, and the property and steel sectors are of particular concern, according to S&P.

Worries about the risk in China's corporate debt have intensified in the past year. Economic growth has slowed and borrowing costs have spiked periodically as Beijing sought to discourage lending to industries saddled with overcapacity and discipline banks that have lent aggressively to riskier borrowers.

Earlier this year, China allowed a Shanghai-based solar-equipment maker to default on a bond traded in the mainland. It was the first time Beijing allowed a domestically issued corporate bond to default.

"We expect more defaults in the steel sector. An external spillover from this has been the more than 25% fall in iron-ore prices this year," S&P said.

Writer: Shen Hong at hong.shen@wsj.com

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

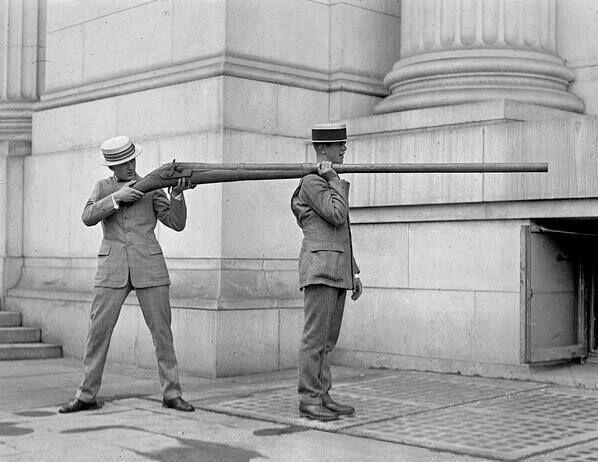

A punt gun; an extremely large shotgun used for duck hunting in the 19th and early 20th centuries. pic.twitter.com/7NAeW56j2u

Saturday, June 14, 2014

The News: A User's Manual

How could the news be different? And are we headline junkies? Alain de Botton thinks he has the answers

Ian Jack

The Guardian, Wednesday 29 January 2014 08.00 GMT

The News: A User's Manual by Alain de Botton – review

Applicants to become trainee journalists on the Scotsman group of newspapers in 1965 took a test in which they were invited to imagine themselves as editors of the Edinburgh Evening News on a day when three big stories broke. One, man lands on moon! Two, Princess Margaret gets divorce! Three, Edinburgh council rates to double! As a possibility, the third seemed far more likely than either of the first two – reader, how little we knew – but likeliness wasn't the issue at stake. The question was: to which story should the editor give top priority on the front page? Obviously the first reflected a momentous human achievement, no question, but the second would be truly shocking, this not yet being an age of royal divorce, while who could doubt that hard-pressed Edinburgh ratepayers would be most materially affected by the third? Our examiners may not have put it in such terms, but we were being asked to decide which front page would attract most attention and sell most copies.

The News: A User's Manual

by Alain de Botton

De Botton plays a similar game in his book, reprinting headlines – real ones – and inviting the reader to consider why, for example, "Sydney man charged with cannibalism and incest" is a more attractive story than "Tenants' rent arrears soar in pilot benefit scheme". The author wonders if our dash to read the first and not the second, to prefer distant sensation to local information, shows that at heart we are "truly shallow and irresponsible" citizens, or if the blame lies with journalistic convention and its "habit of randomly dipping readers into a brief moment in a lengthy narrative … while failing to provide any explanation of the wider context", rather as if Anna Karenina (the example is De Botton's) could be expected to hold an audience if it were serialised in 100-word chunks. It is De Botton's contention that, "properly signposted" (whatever that may mean), the rent arrears report would stand revealed as "part of a hundred-year debate about whether welfare lends its recipients dignity … a single episode in a multi-chaptered narrative that might be called 'How Subsidy Affects Character' [or] 'The Psychology of Aid'". And, therefore, nearly as rewarding a read as Tolstoy.

De Botton thinks news should be more like novels, but what does he think news is? "The determined pursuit of the anomalous," he writes at one point, before deciding that he wants to leave the definition "deliberately vague". Whatever news is, he thinks, along with Hegel, that it has replaced religion as a modern society's source of guidance and authority to become its "prime creator of political and social reality". He also thinks there is too much of it and that we have become addicted – news junkies – and need to recognise its ill-effects, including the "envy and the terror" it promotes; hence what he calls his "little manual", which he hopes will "complicate a habit that, at present, has come to seem a little too normal and harmless for our own good". Other writers might have chosen "illuminate" rather than "complicate" as the verb for the book's aspiration, but as it turns out De Botton's word choice is perfect.

Complications abound. Investigative journalism, for example: the writer thinks that what he calls a "proper" conception of investigative journalism should "start with an all-encompassing interest in the full range of factors that sabotage group and individual existence", including mental health, architecture, leisure time, family structures, relationships … the list goes on, and sounds remarkably like the everyday components of modern life. Should journalism investigate modern life? Most of us believe that, for better or worse, it already does. What De Botton is attacking is journalism's propensity for easy targets, reinforcing our impression that we are ruled by crooks and idiots, while it fails to scrutinise the institutional flaws that have caused them. Of course, his attack has justice, but his verbal imprecision makes his argument hard to figure out.

The author gives a good impression of living in an older and more privileged world – he seems oblivious, for example, to the popularity of media studies in schools when he regrets that "we are more likely to hear about the significance of Matisse's use of colour than to be taken through the effects of the celebrity photo section of the Daily Mail," which is his way of describing the online Mail's "sidebar of shame". He doesn't seem comfortable with the new information age. The comment threads attached to online journalism may indeed reveal "a hitherto unimaginable level of anger in the population", as any journalist can attest (and with more vivid examples than this book provides), but journalism that has been liberated from the constraints of paper and broadcasting slots has great advantages, too. The "multi-chapter narrative" that De Botton believes news needs already exists via search engines and hyperlinks embedded in news reports. The reader can construct a narrative that will end only when his curiosity runs out; nobody else need do it for him. If "How subsidy affects character" is what he's after, the world is at his fingertips.

But De Botton isn't too interested in modern developments. He sees news as a monolith rather than something that changes from place to place, from reader to reader and time to time. The rent arrears story, for example, might play differently in the Guardian and the Sun (if it played in the Sun at all) and wouldn't be a prime example of dullness to everyone: a worried buy-to‑let landlord in Southwark could well find it more gripping even than nephew-eating in Sydney.

Apart from never quite deciding what news is, De Botton is also remarkably uninterested in who pays for its gathering and transmission, and who defines it. A kind of fluent ignorance is at work that might be innocence in disguise. He reckons that our news-checking habit arises out of dread: "the possibility of catastrophe explains the small pulse of fear we may register when we angle our phones in the direction of the nearest mast … a version of the apprehension that our ancestors must have felt in the chill moments before dawn, as they wondered whether the sun would ever find its way back into the firmament". But is dread really what we feel when we turn on the news? It may have been during the last world war, which was when broadcast news turned into a British addiction, but surely we look forward to it now mainly as a form of entertainment or distraction, to satisfy an unfocused curiosity about "what's going on".

The most dramatic and memorable news events are rarely cheerful, and De Botton is far from the first person to wonder if the news gives a distorted, disproportionately gloomy view of human affairs. "Man abandons rash plan to kill his wife after brief pause" is, as he says, the kind of headline you will never read, though not (as he implies) because newspapers have no taste for "good news" but because public events such as court trials ("Man murders wife") make news, while changes of heart, being private, do not. Still, the critic shouldn't scoff at what De Botton describes as his book's utopian project, which is to challenge our pessimistic assumptions about what news is and imagine how could it be. The British nation, he writes, "isn't just a severed head, a mutilated grandmother, three dead girls in a basement … trillions of debt of debt". It is also "the cloud floating right now over the church spire, the gentle thought in the doctor's mind … the small child tapping the surface of a newly hardboiled egg while her mother looks on lovingly, the nuclear submarine patrolling the maritime borders with efficiency and courage …"

Humphrey Jennings could have made a documentary about this lyrical passage, which has a wartime ring to it. The quiet poetry of everyday Britain and so forth: blackbirds sing while Lancasters drone overhead. And when De Botton writes that one of news's main tasks is "constructing an imaginary community that seems sufficiently good, forgiving and sane that one might want to contribute to it", he might as well be writing for the Ministry of Information in 1944. The aim, then as now, is admirable, but at the first tap of the spoon on the egg, the first shot of HMS Imponderable butting into the waves, a little voice will tell us that we are watching the state's propaganda.

On the question of journalistic practice, De Botton is at his most interesting on the job of the foreign correspondent – "interesting" in that the same paragraph can combine a nicely expressed insight into a problem with a monstrous stupidity as its solution. As he rightly says, reporting gives us an unbalanced view of abroad, especially of countries beyond Europe and North America, because it concentrates on political crises and natural disasters, and unless we have some sense of "what passes for normality in a given location, we may find it very hard to calibrate or care about the abnormal". So how does the reporter in, say, Zambia interest his Manchester reader in the Zambian everyday? De Botton thinks it permissible for "creative writers" to adapt a fact or change a date because they will understand that "falsifications may occasionally need to be committed in the service of a goal higher still than accuracy: the hope of getting important ideas and images across to their impatient and distracted audiences".

A goal higher than accuracy? In a book about the news, even one written by an author who cannot decide what news is, there can be no more dangerous form of words.

Source: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jan/29/news-users-manual-alain-de-botton-review

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Blue Planet Society

Blue Planet Society

History In Pictures

History In Pictures